AMDG

Uganda

For a wordy, protracted, overly-dramatic, yet thoughtful and sincere preface, along with a note from Pope Francis, click here.

For a more concise version of a similar message from The Onion, click here.

For an appeal for mercy, click here.

The goals:

1) To write about the most important aspects of Uganda and the world and life and Jesus and my gratitude for you all and everything else.

2) To write once a day, even if briefly.

3) To include some pictures. A note about the ethics of photography.

The reasons:

This is an attempt to make sense of the otherwise unaccountable fact of my presence in Uganda. Lots of people (among them, Bob Pfunder at ND’s Common Good Initiative, and Denis Kidde and Rose Kiwanuka with the Palliative Care Association of Uganda deserve special mention) have gone to lots of trouble to arrange the trip. My best hope at redemption is to convey some manner of insight. I will certainly try to do some good in Uganda, but the chances of success are slim at best. By the end of the trip, I hope that it can be said that I was here because you couldn’t be.

Oh, and some of you requested this.

The setup:

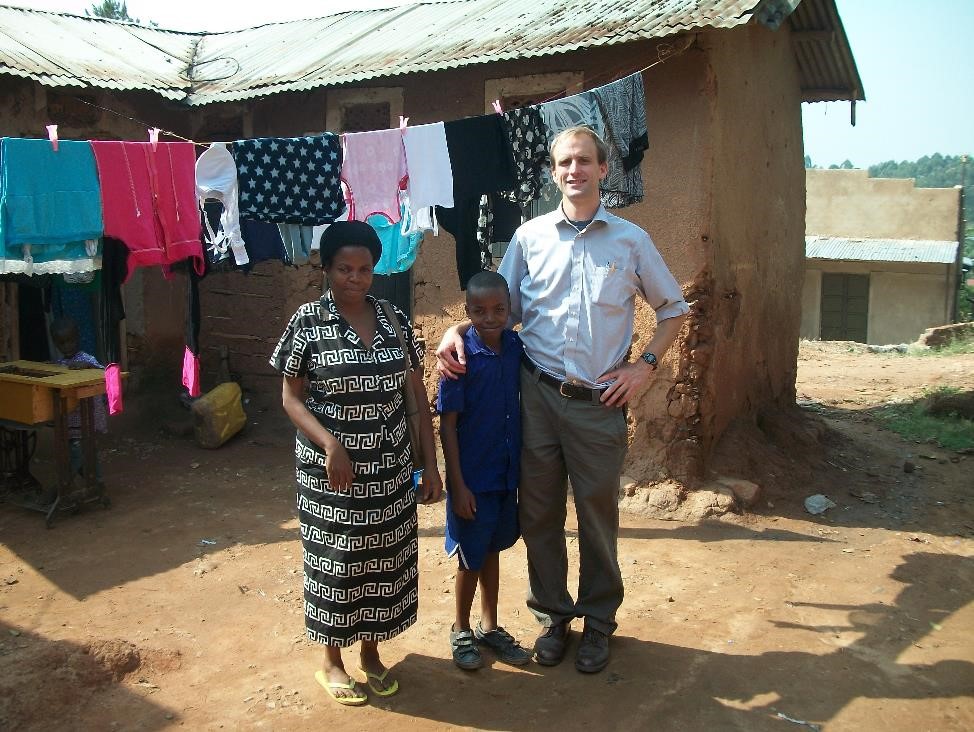

I will be in Uganda from 5.12.14 until 7.15.14. My official title while here is Intern at the Palliative Care Association of Uganda (PCAU). I will spend my first week in Kampala, getting oriented to PCAU, Uganda, a new time zone, being decidedly white, etc.. I will then spend a month in Jinja and then three weeks in Mbarara working in both places with PCAU’s affiliate hospice and palliative care centers. The exact nature of my work will unfold in the future and on this page. My work here was generously, and inexplicably, funded through the immense generosity of Notre Dame’s Common Good Initiative under the direction of Bob Pfunder. I deeply hope that I can prove myself, even in just a really small way, worthy of the gift. For a brief word about Uganda, including a map featuring the aforementioned cities (along the southern edge of the country), please click here.

5.12.14

Arrived in Kampala. Flight technology is wonderful and absurd. The secure zone guard with a big machine gun lent me his cell phone to call my ride. Hopefully this is typical of the country; by all accounts it is.

5.13.14

Shopped for essentials in downtown Kampala. Traffic, fumes, and street-vendors abound. A dearth of open spaces, the lack of an apparent city plan, and pervasive disregard for traffic laws contribute to a sense of confinement and chaos. On first exposure, the city itself lacks charm, personality, and interest. The people, on the other hand, are friendly, warm, and make good eye-contact. They are at the same time youthful (Uganda is the youngest country in the world; 77% of its population is under the age of 30) and slumped (Ugandans are, perhaps relatedly, the least-employed; the rate of joblessness between the ages of 15 and 24 is 83%). The streets teem with healthy, intelligent-looking, well-dressed young people working as motorcycle taxi drivers and street vendors; hordes of people working way below their potential.

5.14.14

Big Day. Orientation at PCAU, the organization with whom I am interned. It turns out that morphine is the name of the game; PCAU is dedicated to bringing government-purchased, nurse-prescribed liquid oral morphine to all in need throughout the entire country. If PCAU is successful, then morphine will become the opiate of the people. Among the PCAU patient testimonies: “It is my savior.” And the main goal, according to the Program Director, is to “preach the gospel of palliate care.” The gospel is that proper pain control with oral morphine can alleviate terminal suffering.

My internship is undoubtedly a splendid opportunity. PCAU and its partner organizations have been extremely effective in their mission (0/112 districts enjoyed morphine-based palliate care in 1993, and 83/112 districts enjoy it now); it will be a privilege to learn from their exemplary efforts.

There are a couple of questions that have been bugging me throughout my orientation. They should be taken in no way as a critique of the organization; the questions are matters of individual, not corporate, responsibility. They fall into two broad categories: 1) The role of suffering at the end of life, and 2) the role of faith at the end of life.

What is the role of suffering at the end of life? Is there any sense, even if a very vague one, in which suffering is somehow important and should be preferred to narcotic release? As soon as I say this, I realize that it is probably the height of naïveté and presumption to make normative conjectures about how people deal with their pain. Nonetheless, I have a nagging sensibility that suffering can be purifying and redemptive, and that it would be somehow problematic to relieve it completely. The sensibility might be a holdover from related deliberations about euthanasia. While terminal narcotic care and terminal killing are surely two entirely different phenomena, some similar considerations seem to attend each. …OK, scratch the comparison with euthanasia. I just read a splendid article on the USCCB website that answers my questions almost completely. Read it here if interested. The main point: pain control with morphine at the end of life can be decisively distinguished from euthanasia, and is a really important part of good medical care. More about this later.

I must wrap up and hit the hay. The other question, about the role of faith, will have to wait. Stay tuned…

Jogged to Mass this morning. Gorgeous singing. Might try to record some of it for a future post. Also, at the elevation of the Precious Body, and then again at the elevation of the Precious Blood, the congregation gave a round of applause. Yes.

Some pictures:

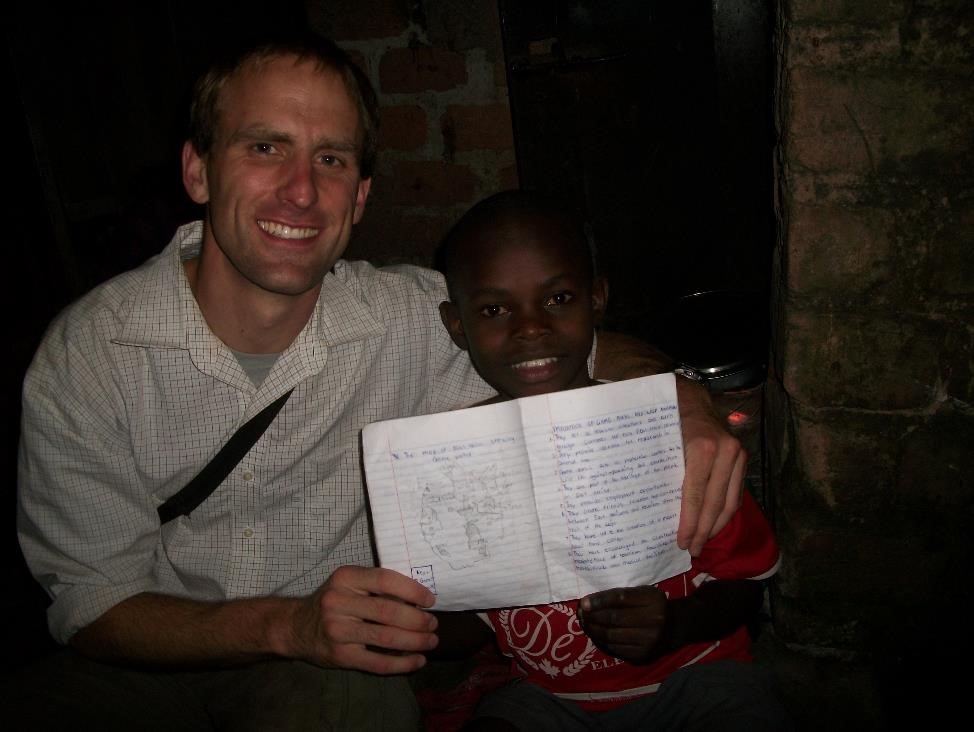

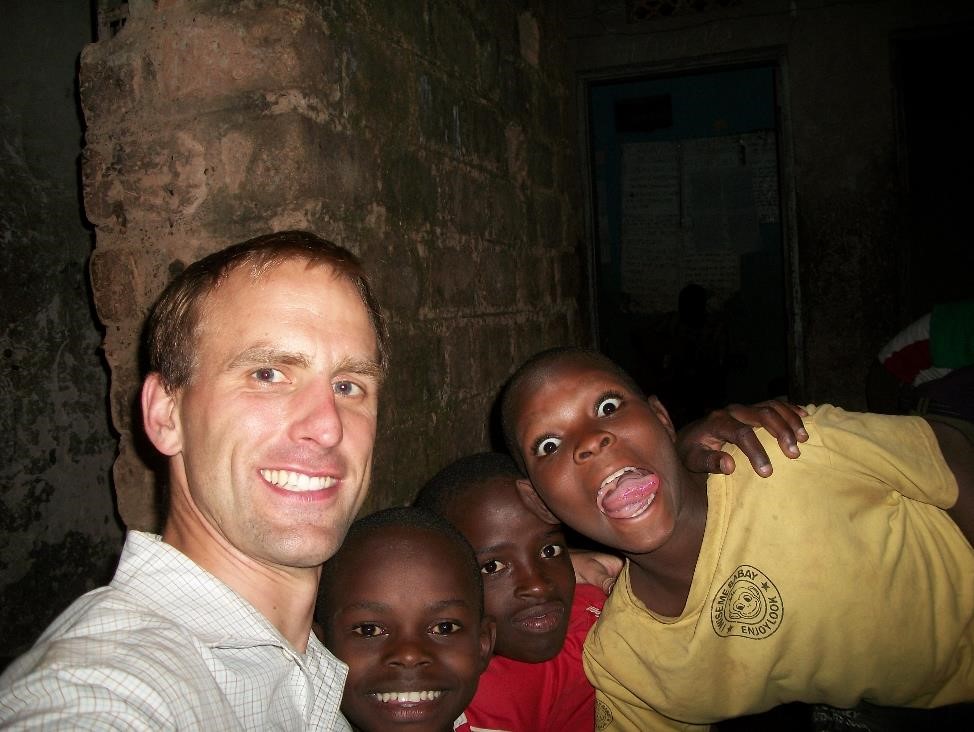

The neighbors and me at leisure. From left to right, Joel is reading his favorite book, namely Genesis. Eric prefers St. John Chrysostom’s On Wealth and Poverty. My newest Muslim friend, Shafiq, The Imitation of Christ. And I am finishing The Power of One, which is, as it turns out, One of the finest and most Powerful books ever written. After we read, hanged out and ate some chapatti, the dudes took my roommate (Graham, a fellow ND student doing a month of research on medical stuff. Good guy.) and me on a tour of the neighborhood haunts, to include the local charcoal stove factory where Joel’s dad works. See pictures of stoves below. More, perhaps, on the factory soon. The posse members in addition to J, E, and S are named Danielle (5ish) and Daisy (3ish). Please pray for them.

Featured prominently in the PCAU waiting area, where religious art would be in a Church parlor, or a giant logo would be at a corporate headquarters, is a portrait of morphine distribution.

5.15.14

Hospital Day. We (Graham and I) visited Mulago Hospital, Kampala’s main public referral hospital. It was a tremendously valuable experience. There are many aspects that I would like to write about at length, but time is short so I will provide some brief quips and a pic instead. The most striking difference between Mulago and an American Hospital is that the patients are primarily cared for, not by nurses or docs, but by their own people. Here is a pic of a typical ward (from cccuganda.blogspot.com):

The people in the foreground on the floor are caregiver relatives and friends. They camp out in the wards, sometimes sharing the same bed as the patient. Since they are not allowed on some wards, they often hang out just outside of them, lining the hallways and crowding the more capacious stairwells. While this is surely a terrible inconvenience, and sometimes an impossibility, for people who live hand-to-mouth and for whom not working can mean starvation, the effect at the bedside is, on the whole, quite humanizing. While the challenges of tending to a loved one in the hospital are surely great, the work (of mercy) prevents depersonalization, which is one of the plagues of American medicine. Today, we met an elderly woman dying of cervical cancer, along with her teenage granddaughter who was caring for her. The girl’s presence seemed to change the dynamic entirely. From the practitioner’s perspective, it would have been almost impossible to reduce the patient to a bed number or a disease entity or something like that; her granddaughter was proof against clinical analysis (from the Greek for “cut up”, in other words, “person-chopping”) and corporate commodification. The patient’s personal identity as grandma, lover, and beloved became unforgettable. From the patient’s perspective, her granddaughter’s presence staved off loneliness and despair, the same demons that attend so closely the isolationist policy in America. The woman, though exhausted, withered and bedraggled, was not sad. She smiled genuinely, from the inside, at moments, and seemed, I guess you could say, undaunted and whole of soul. I doubt that she would be so if she were alone, as so many patients in our country are.

There is much more to say. I hope to get to it soon. Thanks for reading and following this whole thing with so far. I hope that it helps somehow. Please email with thoughts.

5.16.14

I had the pleasure today of lunching with Michael, a founder of Africa’s first and only Catholic Worker. The convo could have been entitled Lost in Translation: Why the Catholic Worker Doesn’t Abroad. Here are a few key points:

1) Americans have extra stuff and Ugandans don’t. Food, clothes, money, time. Lesson: The Catholic Worker depends on economic excess.

2) Similarly, Americans are into giving homeless people stuff, while Ugandans are not. They see it as ridiculous that able-bodied people should eat for free while many others starve. Not only that, but the sloth induced in this manner is harmful to the homeless and to society.

3) Americans can say whatever they want and Ugandans can’t. I asked Michael if the Worker here engaged in political activism, whether he did war resistance, tax evasion, etc.. He laughed. If someone questions the government here, they get beat up (badly) and put in jail. It turns out that dictators are really touchy. Especially when they are trying to keep up the appearance of democratic mandate. A man named Museveni was elected to a five-year term in 1986 and is still the president. By anecdotal accounts, approval ratings are low. These demagogue types are sort of insecure, don’t get jazzed about constructive criticism, and fail to see how cool protests can be. Lesson: The Catholic Worker’s contrarian swagger is predicated upon a relatively functional democratic milieu.

4) Americans are into spending a few years doing “service,” while Ugandans look for jobs. Where money is tight, competition is fierce, and you don’t get ahead by hanging out and helping poor people. The parents, especially, find it absurd that their kids, for whom education is extremely expensive and for whom the parents sacrifice endlessly, should use their most productive years in such a silly manner.

5) Not all Americans want to get married, whereas for Ugandans to be unmarried is to be incomplete and unsettled. According to my PCAU colleagues on a long car ride today, nobody takes people seriously until they have kids. And preferably lots of them. The CW lifestyle is not conducive to procreation.

There are probably a few more points that I am not recalling at the moment.

The history of the Uganda Worker is educational. The entity was apparently conceived by a couple of m’zungu (whities) in 2011 who preached the vision, got things moving, and then left. And then said that they would support the CW and didn’t. And then lots of CW’ers in the States apparently told Michael to keep plugging, even without a lot of support, because, well, many Catholic Worker communities struggle at first. So Michael is still at it. There are surely other sides to this story, and I would be delighted to hear them. I guess the moral of this story is the old “love in action” bit.

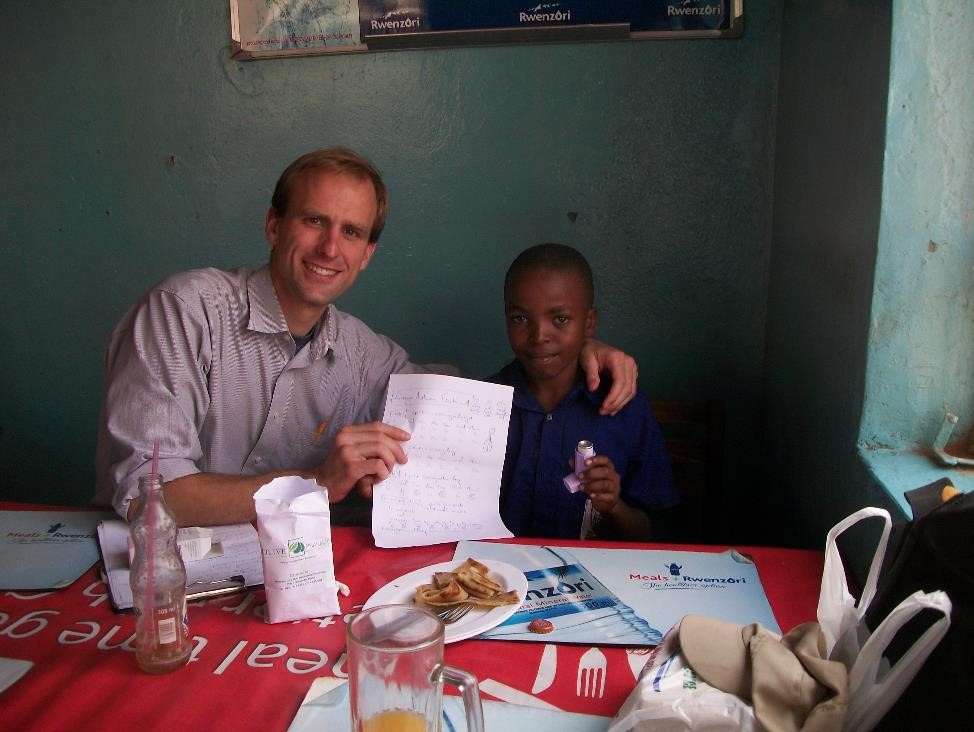

Now, could Michael have been just buttering me up for a fat donation? Sure. Did it work? Absolutely. Even if it was a whopper, though, it was a good one with some good lessons that were probably worth the price of admission, and it’s pretty cute for me to be able to say that I met Africa’s only Catholic Worker. I got a picture too:

I spent most of the day at a conference at one of the nicest hotels in Uganda (see background above; voluntary poverty is not a concept here). It was a summit of some of the main players in the African palliative care scene. They were trying to pass legislation that gave them more bureaucratic support and a stronger governmental mandate. It was boring and fascinating at the same time. The presentations were difficult, but the social dynamics were rich. Basically, it was an attempt at implementing a Western societal convention, The Bureaucratic Meeting, in a radically unconducive environment. I found it hard to follow what the people were saying, not only because the English was heavily accented, but also because the thought processes were difficult to follow. They lacked the logical coherence and linearity that make statements go smoothly into my bureaucratically-formed mind (What is the classroom, after all, but an exercise in bureaucratic procedure?). It felt like people from various particular coherent local tribal traditions and modes of interaction, expression, thought, and dress were forcing themselves into Western bureaucratic conventions, social, verbal, mental, habilimental (please email if you can replace this made-up word with a real one) and otherwise. The effort was stilted and violent.

I suppose that the incapacity to assimilate smoothly to (Nietzschean?) bureaucratic culture is rather a virtue than a deficiency. So the folks are bad at meetings. Good for them. They have ways of being and interacting and communicating that resist foreign imposition. Perhaps many of us who have been formed in the ways of the West would stand to benefit from trying to retrieve those aspects of our traditions and cultures and tribes that resist homogenization, deracination, commodification, Americanization, etc.. Especially the Roman Catholic tribe. I hope that it’s not too late.

I realize that I am treading on sensitive territory here, and that my thoughts lack a lot by way of nuance and political correctness. Please remember, though, dear reader, that I am not going for nuance here. This journal is a collection of stereotyped, prejudiced, first approximations. I suppose that there is really no other possible way to say anything about life on first glance than sloppily; making thoughtful, hasty judgments and then revising them later is surely better than having no thoughts and withholding all judgment (I mean to exclude here the condemning sort of judgment, of course). If anyone can help me with the nuancing, I am sure that I stand in great need of it, and I would be delighted for the help.

I just hijacked one of those corporate legalese email disclaimers from an email of a friend who works at JP Morgan and posted it at the bottom of the page.

[A note from the future (6.21.14)]: Back on this day in the journal (5.16.14), I went a bit overboard with a rant about the recent Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Bill. Unfortunately, it came out a bit more strident than I had hoped, and I can’t seem to soften it without being untrue to my convictions. So, I took it down; I didn’t want to blind-side my audience with a polemic among otherwise polite and relatively innocuous observations. There are a couple of paragraphs, though, that are only pertinent to the Bill by way of back-grounding, that are not terribly controversial, and that bear on the Ugandan experience more generally. I excerpted them here in case they help.

“…In order to understand the importance of the retributive Western response [to the Anti-Homosexuality Bill], some words about foreign assistance are perhaps necessary. Foreign aid is a narcotic here, and the whites are the dealers. When people get hooked on drugs, they forsake the relationships and modes of existence that sustain them. So it is with the Ugandans and their traditional relationships, cultures, and native institutions. When people turn towards the aid-dealers to get their fix, they turn away from their ancient tribal social structures, the institutions that give them life and identity, meaning and satisfaction. By the time the dealers lose interest and pull the plug, the relationships have often changed and the structures eroded. Whereas people were poor before, now they are destitute. In the case of the anti-homosexuality stance, it’s a big price to pay for displeasing the masters.

It doesn’t help that the psychology of the Western do-gooder is quite complicated; his reasons for engaging in the aid relationship are profound and mysterious, even to himself, and his reasons for leaving the relationship are similarly complex. The overall effect is that the m’zungu (Ugandan for Whitey) is a fickle and unpredictable beast. The problem for the Ugandan is that the sense of gratification that most Westerners get from doing good over here is not enough to sustain them in a long-term relationship, with the effect that they are rather more like dealers than true patrons or loyal friends. (I will go ahead and try to riff for a bit about the psychology of assistance, even though I am sure that it is much more complicated that I can imagine, and much-better-treated elsewhere.) It’s really nice for Westerners to feel like we are helping people. In fact, there is nothing nicer. We Westerners all have this holdover sensibility from Christendom that we should serve the poor and vulnerable. Secular atheists, Catholics, Protestants, hipsters, John Wayne, Flipper, vegetarians, casual Buddhists, and spiritualists alike, almost everyone in historically Christian countries thinks that it’s a really good idea to go help really poor people in all corners of the world. When you ask the Western atheist do-gooder why he is doing good, he will make a circular proposition, like he is helping people in order to help people, or he is going good, just, you know, for sake of going good. And helping people. If one really pushed it though, and really tried to get to the bottom of things, I thing that one would find suppressed Christian premises. One corroborating bit of anecdotal conjecture is that the globe-trotting impulse doesn’t really seem to pertain in non-Christian cultures. Muslim and Hindu cultures come to mind. They might have a great ethic for dealing with their own, but I can’t imagine that something like the Good Samaritan story would have a lot of meaning in these contexts. In most cultures, the “neighbor” is literally the guy next door, not the guy from a different country and/or caste. I haven’t encountered any Muslims doing aid work, or at least the kind of aid work that the Westerners do, and the widespread sentiment among the Ugandans are that the Hindu Indians are here for business, to make money. Westerners, on the other hand, come to Africa in droves because they get a lot of internal satisfaction and external affirmation from exercising their genetic Christian propensity for helping the poor.

This drive to lend a hand surely has many great and salutary aspects, and much if it, in the end is truly sincere, holy, and helpful. The problem for the poor, though, is that dependency is a one-way street. The Westerner can get his satisfaction and affirmation after only a short time with the poor, or by sending an occasional check if and when he can afford it and is feeling generous. The poor person, on the other hand, cannot get free food, water, medical care, money, and advice without the Westerner’s assistance, and his need is constant. The experience of helping the poor for a few weeks or months is enough to buoy the Westerner’s ego and pad his resume for the rest of his life. The experience of receiving help for only a few weeks or months leaves the poor person in need, sometimes a greater need than before the intervention. The strength of motivation in the aid-recipient relationship is grossly lopsided. The Westerners’ reasons for withdrawing aid can be trivial, whereas the recipients’ need for intervention always remains grave. Western support is fickle because it is driven by a desire that can be easily satisfied, even without actually accomplishing anything. It is often enough for people to only love in dreams. The Westerner can run from the poor for any number of reasons; because they get annoyed, because they get bored, because their excess money runs out and in order to continue they might actually have to sacrifice some aspect of their rich lifestyle, because the poor are not grateful enough, or, sin of all sins, the poor might take a stand for their families and their youth by opposing a …”

You can see where this is going. I think that the argument might actually have some good points, and that it’s not all actually as vitriolic as I am making it sound. Feel free to ask me about it in person if you’d like; I don’t mind mouthing off about this stuff in the context of friendship. No matter how much I may disagree with a friend, there are ways of communicating these things to their face that preclude animosity. In person, I can state objectionable points while also communicating, in various subtle and powerful ways, how much I love and admire my friend. This is impossible over the internet. I have long thought that people never really change their minds outside the context of friendship. People only really listen to someone if they think that that person loves and accepts them first. Public diatribes, many academic exchanges included, are for the gratification of the zealot and for the indulgence of people who already agree with him. They rarely, if ever, lead to benefit or conversion. In fact, impersonal, public rants usually have quite the opposite effect of polarizing and alienating the people who might gain the most from conversation in the context of warm and caring friendship.

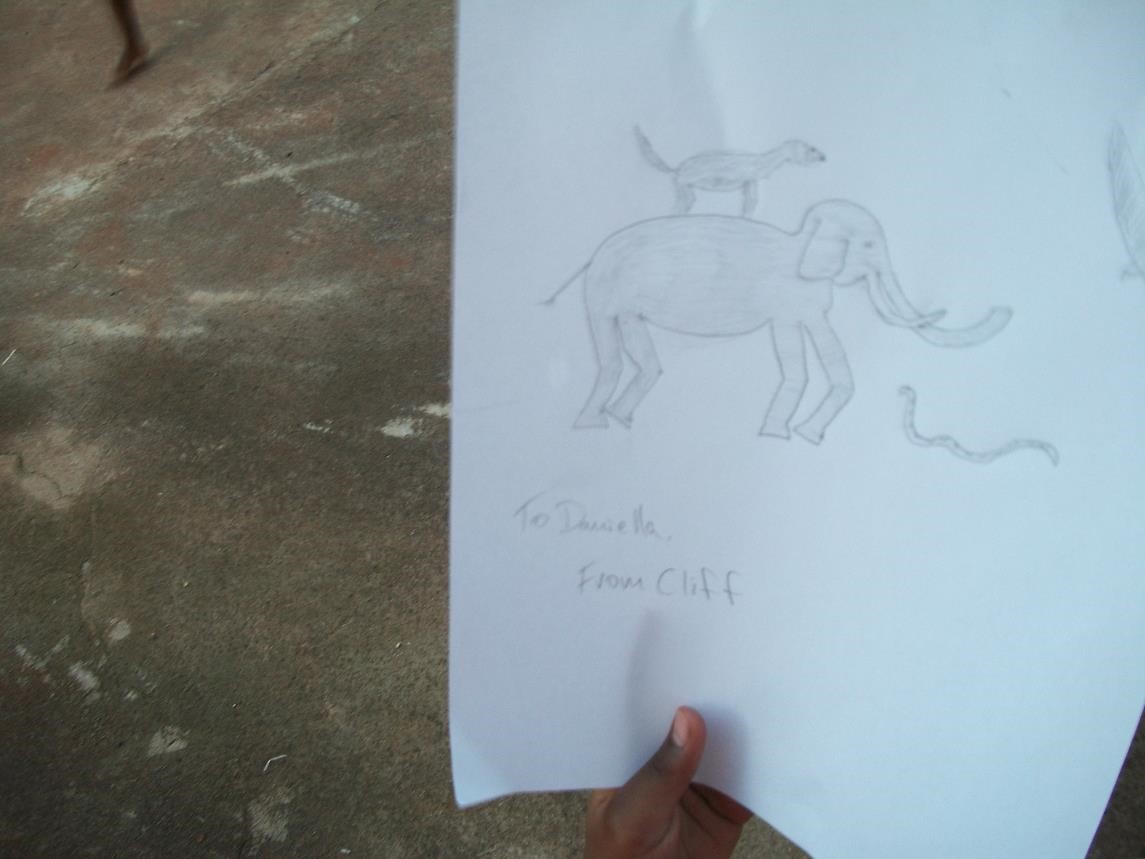

Pic from the day:

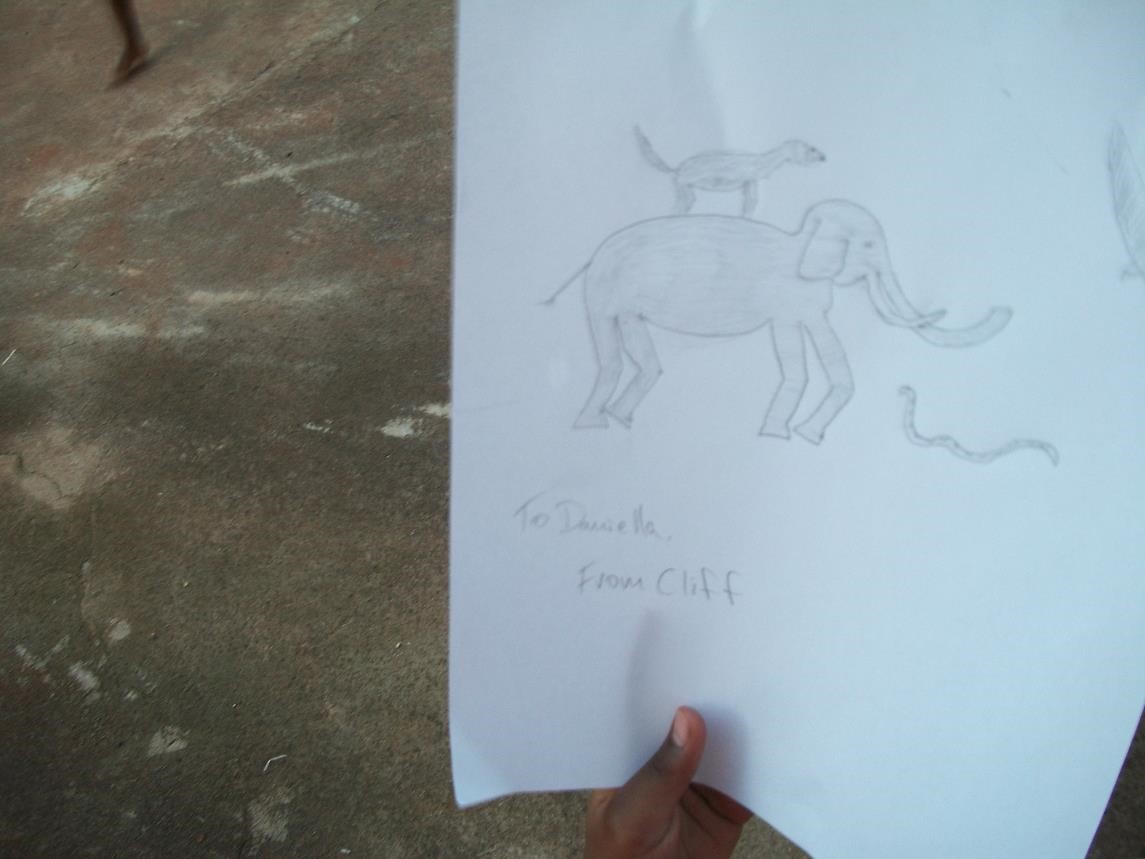

The portrait that I drew for Daniella (5yo) during neighborhood kiddo activity time today. She kept on demanding that I draw various animals, and this is the menagerie that materialized. It’s a picture of a snake attacking an elephant that is counterattacking the snake, but only at the behest of the terrier that is riding the elephant while an eagle swoops in to finish whatever carnage the elephant manages to initiate:

5.17.14

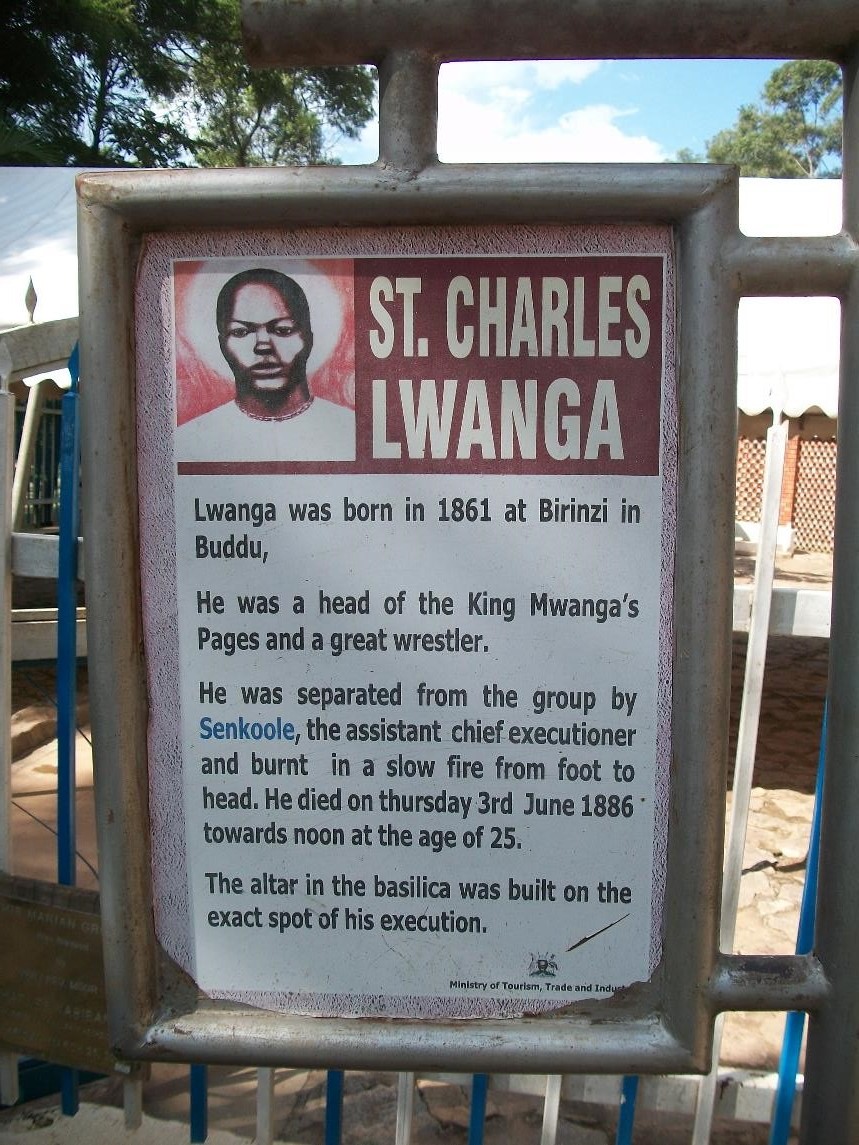

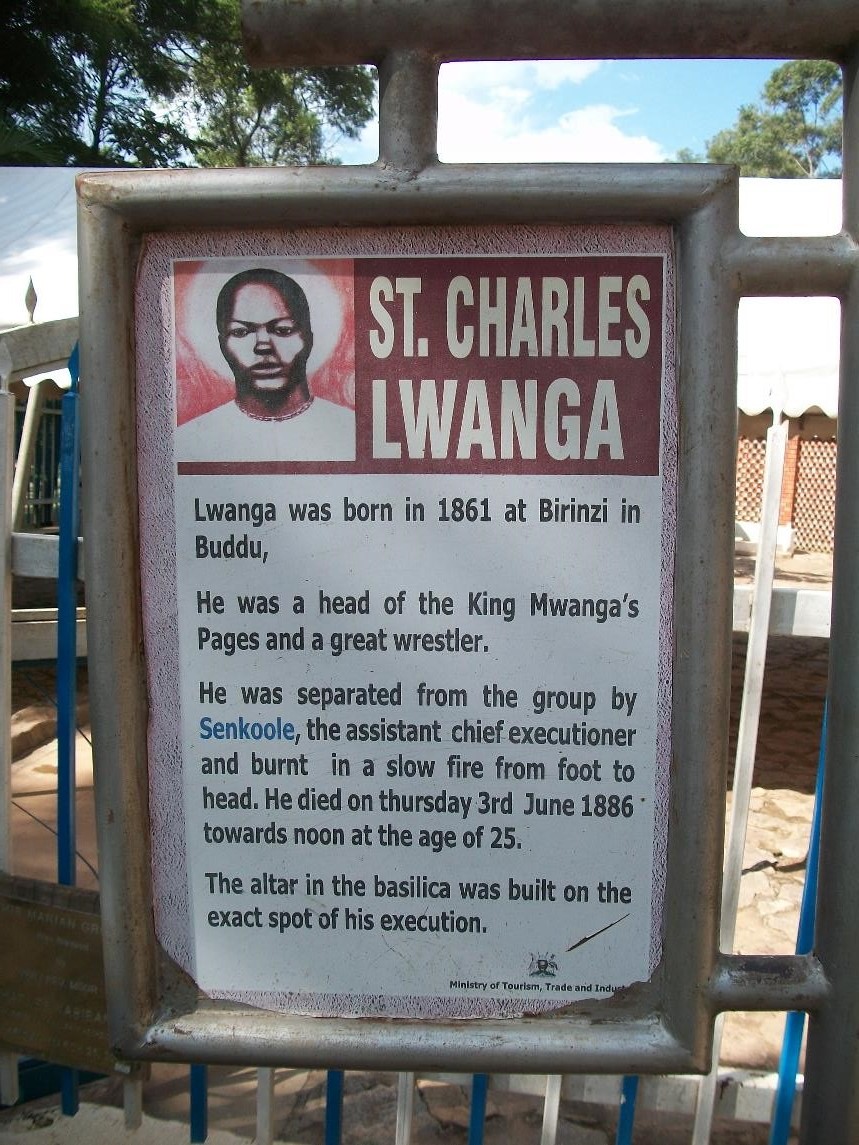

We went to the Uganda Martyrs’ Shrine in Namugongo today. The main mission was to fetch a relic at the request of my friend, Rick. Thanks, Rick, for the motivation; it was a good trip to make. Here is a brief history of the martyrdom, from America Magazine. Here are some profiles of the martyrs. The America article is worth a read; I will rely on it instead of doing my own recap here. The lesson is succinctly stated by Charles Péguy: “Life holds only one tragedy, ultimately: not to have been a saint.” Uganda martyrs, PRAY FOR US!

A few pics:

The sign at the front of the Shrine:

The Tabernacle:

A sign with a short bio of Charles Lwanga:

A scene of Charles Lwanga’s burning (look for the bundle of sticks with a head coming out the top; it’s sort of difficult to make out here):

A few aspiring martyrs (Ronald [our car-driving Virgil], Graham [the roommate], yours truly):

5.18.14

Travelled from Kampala to Jinja. Took most of the day. Nothing much to report.

5.19.14

I hit a wall today, especially with journaling. It feels quite lame and self-centered, like I’m just talking to myself and navel-gazing. I might take a break for a couple of days.

Another wall- I checked out from reality a bit and watched a movie on my laptop this evening. The Way Way Back. Pretty good flick. I’d give it an A-.

I suppose that these thoughts have nothing to do with Uganda and poor people and stuff. I am probably doing the escapism thing. Maybe the honeymoon is over, and the difficult stuff is getting to me. Hopefully this will pass and I’ll be able to live into the whole thing a bit more. Maybe it’s a natural and temporary response to witnessing a lot of poverty and suffering. We shall see.

We did do some home patient visits today with Hospice Uganda, the Jinja branch. I need to let it sit a bit before I can talk about it.

5.20.14

This is actually a note from 5.21.14--from the future. Whoa. I didn’t write today because life was really hectic. Graham and I decided to move out of our Jinja apartment that we have been in for the last couple of days because it was pretty rough. Small, stuffy, hot room with lots of mosquitos and ants. The last straw was the really loud TV next door that made it difficult to sleep. Here’s the thing, though. I had a breakthrough of insight at 2:53am, after being really angry and frustrated for a few sleepless hours in my bed. Right after I had the insight, and actually started writing about it, the television went off, at 2:58am to be exact. It was like God was trying to teach me something through the trial, and he wasn’t going to let up until I got it. But then, after I figured it out, the trial stopped immediately. I just regret that Graham had to get dragged through the whole experience.

The next day, I thought about how to present my lesson on this journal. Here it is: My grandparents used to cut out and pin up this little one-frame comic called “Love Is…” that would feature the most sappy and cliché aspects of love being acted out by naked babies with adult facial expressions. Totally creepy and arguably pathological. Here are a few samples:

I thought to write a few observations about what Wealth Is…, but without all of the Freudian baggage of nude manchild comic characters. Here are a few taglines that come to mind based on my experiences over the last few days:

Wealth is…control over your sleeping environment.

Like I said above, cheap apartments mean thin walls and unpleasant neighbors.

Wealth is…beefsteak and mango lassi instead of maize patties and rice.

I lust for protein over here. Most people can’t afford much of it, so I end up spending Western amounts of money for Western amounts of beef at the m’zungu (Ugandan for “whitey,” “cracker,” “gringo,” “The Man,” etc.) restaurants in the area.

Wealth is…a smooth ride.

The roads here are awful, which means that car rides are tremendously turbulent. And slow. Unless your driver is as reckless and skillful as ours has been. James drives extremely fast over very difficult terrain. He is truly an artist at the wheel, a surgeon of the road. He drives with surgical precision, which is important because so many lives are in his hands, especially the lives of the people that he passes within a hairs’ breadth, mostly children. I marvel than he doesn’t clip at least one person a day. It doesn’t seem safe at all to me, but I suppose that I shouldn’t impose my standards…

Wealth is…frequent nursing attention and doctor visits in the hospital.

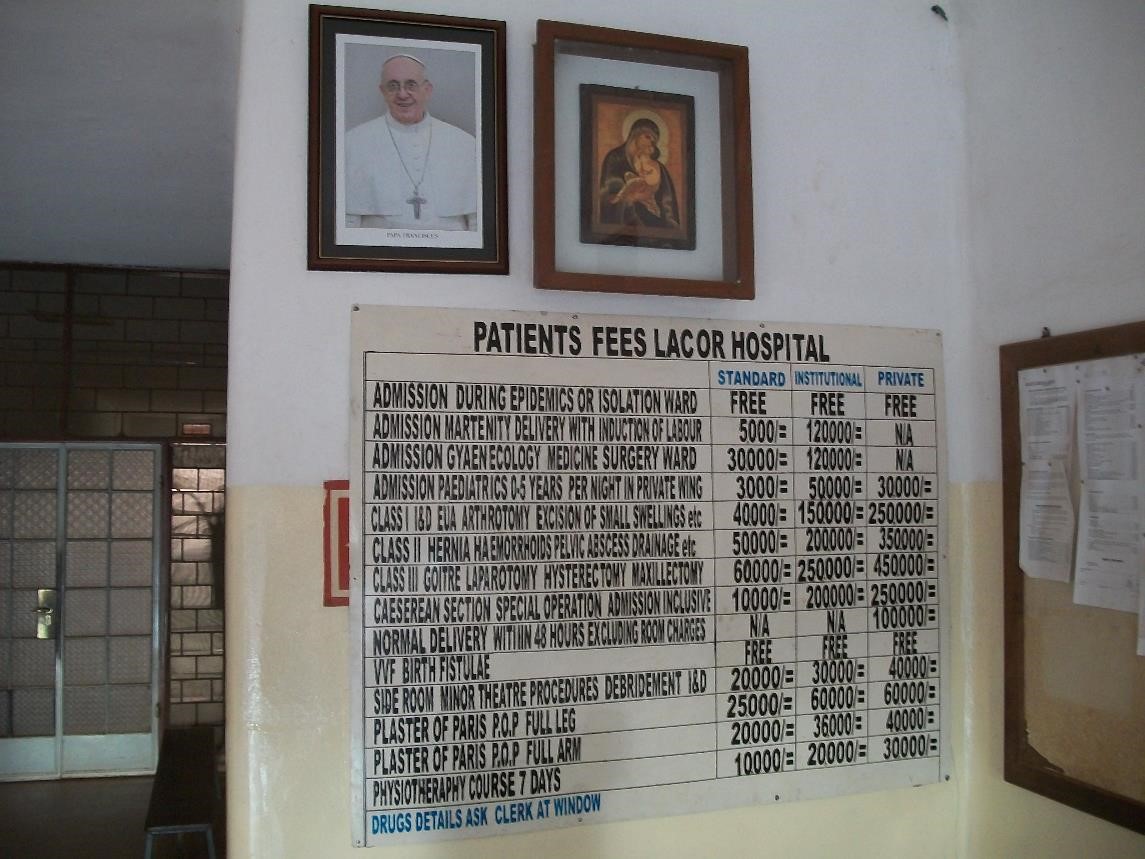

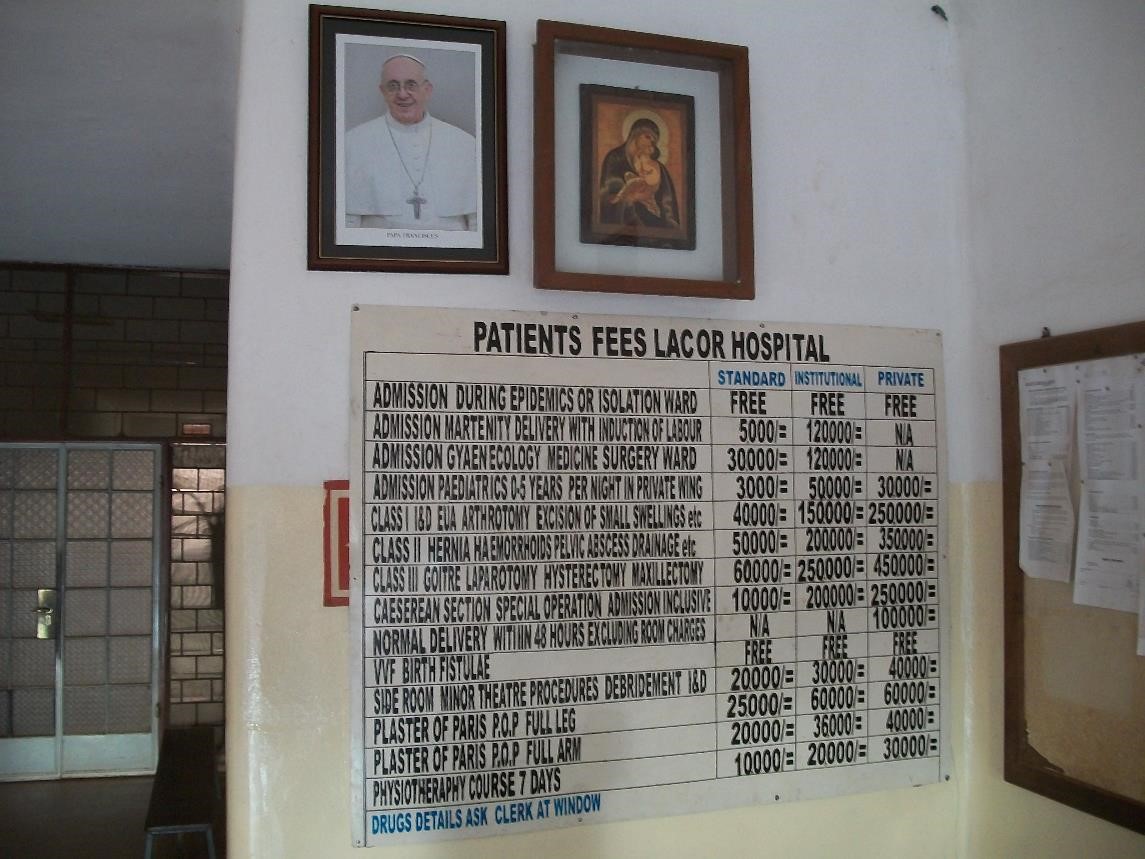

Everybody who has ever had a run-in with hospitals knows that the difference between life and death is a lot of attention, mostly from the nurses. Limited resources means limited salaries means limited attention. If you want good medical care here, you either have go to the public hospital and pay the physicians extra on the side for their attentiveness, or go to a m’zungu hospital, of which there are a couple in the country, and which charge much higher fees.

Wealth is…peace and quiet.

It is difficult for Americans to imagine how relentless and pervasive noise and chaos and stress can be, especially in poor urban settings. In America, we have lots of space, parks, benches, trails, rivers, and cheap, quiet restaurants where we can just sit down and take a deep breath and relax. And everywhere, for the most part, is relatively clean. Not so in most poor countries. There are few public open spaces, parks, natural vistas, benches, etc., and nothing untouched by commerce and disorder and dirt. If you want peace, you pay for it. In each of the towns I’ve been in so far (Kampala and Jinja), there are a couple of little enclaves of quiet and shade and relief, usually at high-end, Western-style restaurants or hotels or golf courses. There are rarely any locals around unless they are serving you, and you always have to pay. I’ve never before so appreciated or been aware of the thousand little things that make for pleasant environments. Maybe this means I’m getting old and soft. Here is a short list of those pleasant-making factors that come to mind as I think of the places I’ve been over the last week, both the dirty streets and the refreshing oases (particularly pricey restaurants): nice views, humble table service (there is nothing more relaxing, even inebriating, than being deferred to), polite manners by other rich customers (what are good manners but the mutual guarantee of a pleasant environment?), lots of space, a line of defense (preferably unspoken and invisible) against the riff-raff (usually enforced by a gatekeeper or maître d’), the absence of needy people (in other words, the presence of other wealthy people), a feeling of security (both bodily and with regard to belongings), aesthetically pleasing and solid architecture, tasteful art, healthful food, shade from the sun, and clean bathrooms. It’s the little things.

Wealth is…good information.

A lot of the patients that we see in palliative care have been thoroughly fleeced by the “healing” establishments by the time that they get to us. By their own accounts (I’m thinking of a patient named Lawrence that I did a full patient interview with yesterday), their first recourse is to the local traditional “healers”--herbalists, witch doctors, etc.. These often unscrupulous practitioners charge significant fees, and convince the people to keep coming back even without results. When the sick are finally out of money, the traditional types cover their incompetence by telling the patients that their disease is such that it can only be cured with a particular talisman that is obviously beyond their ability to obtain, such as a lion’s pelt or something like it. By doing so, the “healers” maintain their professional reputation and prestige; it is the patient’s fault that the treatment didn’t work because they weren’t willing to go the distance. Then the patient might put himself into the hands of equally unscrupulous Western practitioners, a white-coated version of the same scam. He goes into the Western-style medical establishment with his hat in hand and what little money he has left after the first round of fleecing. Instead of providing a probabilistic diagnosis based on patient history and clinical examination, which a skilled physicians can often do in little time and for not much money, the hospital advises the patient to undergo a full battery of imaging and lab tests for his suspected condition. A patient might come in with a classic, no-brainer, presentation of prostate cancer, for example. After spending all of his money on x-rays, PSA, biopsy, ultrasounds, and blood work the hospital issues a judgment that yes, indeed, the patient has prostate cancer. The kicker is that the diagnosis is useless because the patient is now too poor to obtain treatment in the form of radiation or chemotherapy. And the establishment knew this from the beginning because the full course of treatment for cancer, including transportation, food, etc., is about $1500, an unimaginable sum for most of these people. The establishment takes all of the patient’s money to perform a bunch of unnecessary tests to provide a useless diagnosis. The patients come to us, the palliative care folks, with lots of pain, and no recourse to treating the underlying illness. I suppose that we do them some good by lessening their suffering, but it sure doesn’t feel great to see people walking around with conditions that, back home, would be treated and sometimes even cured. My American colleague Graham was relating in the car yesterday, for example, that his grandfather’s prostate cancer was radiated and resected such that his grandfather has been cancer-free for years. My African patient Lawrence, on the other hand, is dying of prostate cancer because he can’t afford to treat it. Not being able to afford good treatment is one thing, but having access to good information and trustworthy medical professionals who could have saved him lots of money and time in another thing. A good doctor could have told him him after a ten minute history and five minute physical exam that yes, you probably have prostate cancer, and no, you can’t afford to do anything about it. Instead, the establishment here produced an identical result, but took him for all he was worth in the process.

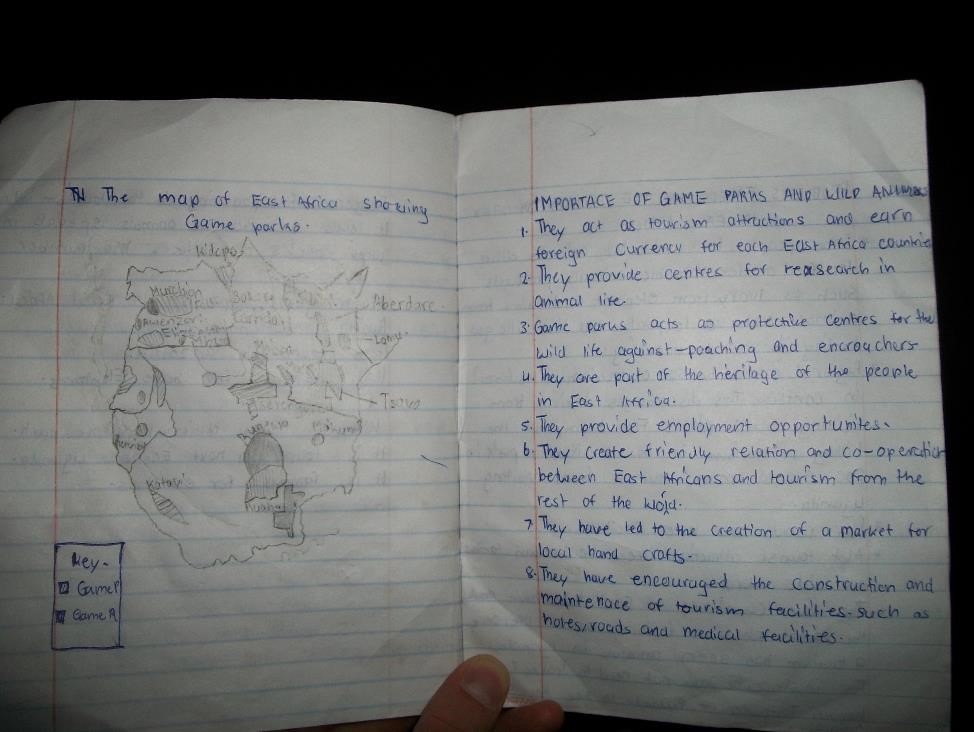

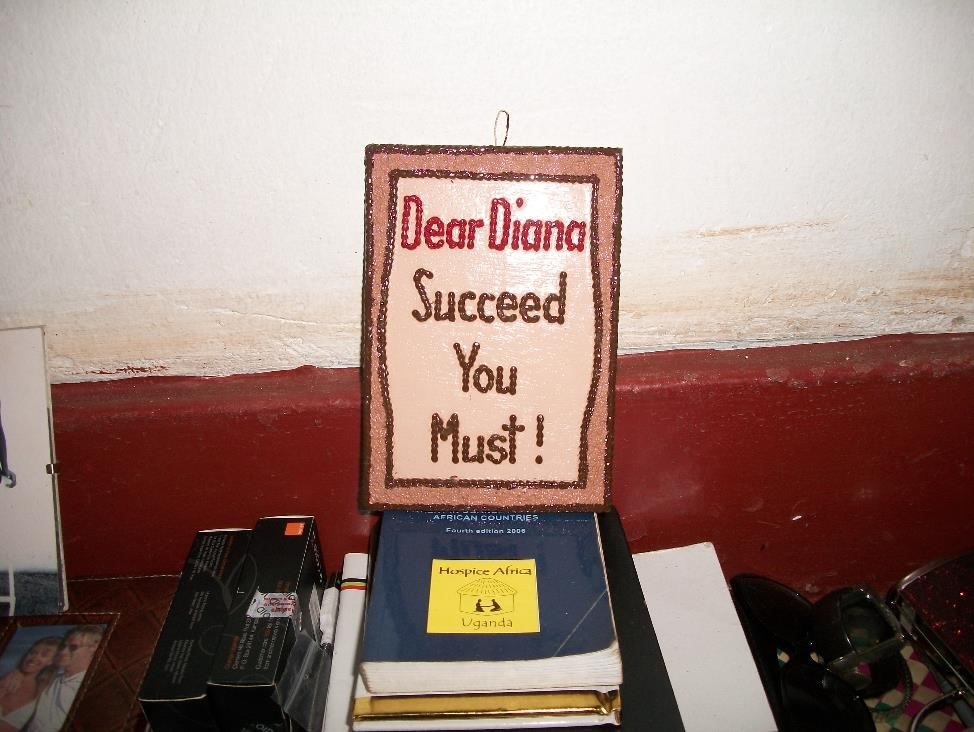

Wealth is…a solid education.

It is probably difficult for us in the West to understand, also, how much an education matters around here. I include a photo of a little placard that sits in our apartment, on top of study guides for a nurse’s licensing examination. The placard belongs to the apartment’s regular resident, who is studying to be a nurse.

I think that this captures pretty succinctly the local attitude towards education. It’s not so much a matter of refinement, or even social status, as much as raw necessity. In an economy like Uganda’s, education is the only way out of one-dollar-a-day manual labor. Whereas in America, a high-school dropout can expect to be able to work hard at a decent job and make enough to feed, house, and educate a family at a relatively high standard of living, a lack of education in Uganda means penury. If someone can afford it education can open a world of possibility. Learning English, for example, gives one access to Western wealth; getting a professional credential is a quantum leap in terms of opportunity. Uganda is clustered along with the rest of Africa at the bottom of the literacy rate list, coming in at about 60%. If one can simply learn to read, one is way ahead of the game. Since an education is the (only) way out of grinding poverty, lots of families give everything to provide their children with a good one. Our driver yesterday was laughing at the fact the police had set up their radar guns along our route. It happens only sporadically, when they need some extra income (in the form of bribes to keep from getting a ticket). The widely-known reason that the police had set up shop during this particular time of year: school fees are due. Educational costs put a lot of stress on families, and scraping for the fees is a well-known phenomenon. The moral of all of this is that an education is utterly important in Uganda and that people sacrifice a lot to ensure a good one for their kids. And I should add that the difference between no education and a mediocre one seems to be almost as big as the difference between a mediocre education and an excellent one. Each leap entails a huge increase in cost, and so education is a means for the wealthy to maintain privilege across generations.

[An addendum from the future] Wealth is…an ad-free existence. The richer you are, the less advertisements you have to look at and listen to. This is true everywhere. Enlightenment and power accompany wealth. Enlightened people realize that, “wait a minute, why am I watching people on television telling me what to buy and do, and why am I looking at billboards instead of sunsets on my drive home from work. This is crap.” And then they change things by turning off the television and radio, reading books and buying music instead, and petitioning their cities to get rid of the signs. The poor are not enlightened. So they watch their two hours of daily TV, which is a form of mind control (Click on the link to read a solid review of a great book about television.), and they passively resign themselves to the ubiquitous radio and billboard advertisements at work, in the taxi, and on the road; they lack the imagination or will to resist the onslaught through either personal choice or political action. It has reached absolutely ridiculous proportions in Uganda. The walls on the streets are painted over with ads. Many storefronts, even in remote little villages, are covered over by national advertisements for Pepsi, Coke, mobile phone companies, and the like. Loudspeakers blare commercials throughout the most populace areas. There is no limit to corporate intrusion and marketing greed. Every aspect of the peoples’ environment is a plaything of the national brands. The government, by allowing all forms of marketing, has sold the souls of its people to the highest bidders.

So what are the folks to do? The assault is implacable; when it comes from all directions, when nobody stands in the way between the corporations and their prey, when it becomes just another part of the culture, how are the poor to resist? I used to teach all subjects to Latino sixth-graders in inner-city Los Angeles. I had to counsel a lot of them about doing homework, and when I started asking them about their home environments, I realized that there was literally no escaping the tube. Every room in their small houses was colonized by the great manipulator. Poverty means getting handled in many ways, but especially by advertisement. People in Marketing should all quit their jobs and spend a few years teaching inner city youth how to read and think in reparation for their opportunistic sins.

This evening, Graham and I moved to a hostel, due to the television problem. Seems like a good place- friendly fellow guests and peaceful accommodations. It’s called Busoga Trust Guest House in case you are ever in the area.

A few more pics:

The apartment with the really loud TV next door:

The driver-artist James and a typical stretch of road:

My salvation from certain starvation:

5.26.14

Just had a convo with Lisa, a Canadian nurse who has been here for a couple of years, and is doing some really interesting work with orphans and their families. The main idea of her organization is to make sure that kids never become orphans to begin with. It turns out that, according to this woman, 80% of kids who become orphans actually have someone who is willing to take care of them, but is prevented from doing so by financial hardship. In addition to this hardship, there is a demand-side incentive to separate kids from their families because it’s highly profitable; orphanages can bring in $5k-$10k per adoption in various fees. Another demand-side incentive is the starry-eyed and naïve attitude of people like me who once spent a few weeks with street boys and now want to start an orphanage and need clientele. So, financial hardship, profitability, and do-gooder naivite combine to needlessly split up families. This woman’s organization focuses on helping families keep their kids by giving them emergency housing for three months, providing social work expertise in order to help stabilize family crises, and otherwise preventing the kinds of pressures that lead to orphanhood. What an astoundingly sensible and excellent approach! Here is the website: http://abidefamilycenter.org/ . And the FaceBook page: https://www.facebook.com/AbideFamilyCenter .

Lisa also affirmed my desire/idea to try to do child and adolescent psychiatry in a setting like this. Apparently two of the most neglected areas of care among the poor in Uganda are addictions counselling and trauma counselling. There are very few people who are qualified to do this kind of work, and it is tremendously important because the need is so great. According to Lisa, almost all of the women in the slums of the bigger cities like Kampala actively prostitute themselves, and almost all of the children who go through orphanages are physically or sexually abused at some point. Additionally, alcoholism is rampant among these families. Lisa’s organization does not take these cases on because they do not feel qualified to handle the intense demands of that sort of work. Hearing her talk about the kids and the ways that abuse affects them was both heartbreaking and made a lot of sense. It takes years, apparently, to even get to a place of trust with the kids from which one can help them shed the denial and defense mechanisms that keep them from processing things. In the meantime, the trauma manifests itself in nightmares, depression, intense behavioral problems, and even medically as failure to thrive. The desire to forget about the pain often, ironically, drives the kids to run away from their adoptive families; the streets are a familiar place, and survival mode, even if unpleasant, feels like home. On the streets, the kids don’t have to deal with the process of learning to trust people and all of the wound-surfacing that accompanies it.

Wow. Amazing stuff.

5.30.14

I am on my way home from an African cultural show. The show featured tribal music and primitive African mating rituals. It all felt forced and stripped of proper context, kind of like being at a zoo. I wonder whether these pageants are rather more misleading than educational, whether they misrepresent African tribal cultures. Phrases that I wrote while watching the show: Jungle dancing, uncoordinated, unskilled, fake smiles, animalistic, base, sad and artificial, inauthentic and zoo-like. The entire show can be summarized as follows: the group of dancers divided up by sex and trapsed around the stage for two hours, each sex demonstrating one of its unique physical capacities. The women chose to demonstrate their capacity for shaking themselves. For two hours. The men exercised their capacity for jumping around. Also for two hours. At various points throughout the exhibition, the two sexes engaged in some sort of ritualistic mating drama. But the interactions were always predicated only on the most unrefined, base, artless forms of physical self-expression and animal lust. At no point did the players hint that they were driven by capacities beyond those of the beasts of the field, let alone by powers of intellect or the soul. Compassion, generosity, wit, culture, art, virtue, intrigue, plot, character, and theme were out; fatpad-shaking and high-jumping were the main orders of business tonight. This was brutality, pure and unalloyed. During the show, I pulled up The Iliad on my phone in order to counteract the corrupting effects of the inanity on my mind and soul. I eventually left early, escaped to our van, and plugged into Beethoven’s Sixth as a sort of emergency shock treatment to reorder my affections and resuscitate my higher faculties. I sincerely hope that the actual tribal traditions are not so base and vacuous, but perhaps they really are.

[Ed. Note: The following paragraphs are a collection of thoughts undergoing a piecemeal process of concurrent accretion and refinement. Contrary to journalistic conceit, I’ve gone back to this section multiple times over a couple of weeks. Some parts are bloated and flabby; others are starting to read with some flow. There are some good thoughts here, but the overall structure is still a work in progress. Please read mercifully.]

The show launched me into a deliberation about the relationship between native tribal culture and Western modernity (It’s not a difficult thing to do; I think about this stuff all the time even without prompting). A particularly harmful dynamic comes to mind. The main players are the average Westerner, the Western caricature of African culture, the African, the political correctness thought police, and Western capitalism. The setup goes something like this: the Westerner absorbs a caricature of African culture, much like the one portrayed on stage tonight and described above. The most current dictates of political correctness proscribe any kind of critique. The Westerner is therefore prohibited either to think critically about African culture, or to wonder whether the image he has is an accurate one. The caricature is sacrosanct and unquestionable. On the other side of the world, the African goes about his business. Whichever kind-hearted Westerners would come to the assistance of the hapless natives are blinded by the sort of caricatured shadow-play that I witnessed tonight, and paralyzed by the fear-mongering political climate that attends American culture, especially around Universities and bureaucracies. The American is lulled to complacency by a false sense of propriety (“I toe the line with regard to race rhetoric, therefore I am kind and good to black people and can comfortably ignore what is actually going on with them”), and does little by way of thinking critically about the problems that face Africans or actually trying to help them.

But why is it important to think critically about African culture? I mean, come on, haven’t we already done enough harm without judging them? The answer is yes. The West has wreaked, and continues to wreak a lot of havoc here. But I don’t think that we would be helping the Ugandan by going hands-off. The Ugandans have a lot going for them; in fact, I will argue that they have a great amount to teach us. But they also, I will argue, still need something from us by way of critique and encouragement. The argument goes as follows: The forces of modernity in Uganda threaten to chop society it into bite-sized individualistic people-chunks for ravenous consumption by the hideous Nation-State-Global-Corporation-Military-Industrial-Complex. Monster. What the West has loosed upon the land cannot be re-caged. It can only be conscientiously resisted. And I would argue that the only force in Western culture that is truly capable of resisting the modernity and the ravenous beasts that follow in its wake of carnage is the power of Christ, especially as it is mediated through His Holy Catholic Church. The local cultures of the various Ugandan tribes have a lot going for them, but they don’t stand a chance against modernity without the Church. Just like Catholics don’t stand a chance against modernity without local tribal culture. We need each other in order to survive.

OK. I know that this sounds far-fetched and tendentious, but hear me out a bit. The threat of the monster is real. Let us call it the Corporate-State Beast. This Beast has the potential to ravish Uganda, as it has ravished America, and reduce everyone to its slaves. Uganda, as most poor countries, is an advertisement feeding frenzy. No vista in all of Kampala, Uganda’s capital and largest city, lacks a prominent billboard or two or ten. You can’t listen to the radio for five minutes without hearing a string of violent, inane commercials that last for longer than the intervening series of songs; the music is inserted between commercials merely as a gesture, an attempt to keep up appearances. The culture of Kampala is comprised of scattered weak rural tribal remnants surrounded on all sides by consumerism. Instead of following the Liberal (both in the classical sense and the recent sense) impulse and “freeing” people to pursue all of their desires (which are easily and often coopted by corporate interests) the Westerner should look to helping them defend against modernity by bolstering the most important and authentic aspects of their own culture and supplementing it with the highest and best traditions that the West has to offer, the traditions that free people in the truest sense, that is, that free people to pursue the Good. The tradition of the Liberal Arts and of Catholic formation come to mind. The alternative is to leave them to the same unredeemed tendencies that once perhaps made for functional pagan society, but now form the basis for manipulation by Corporate-State profit-and-power-motives.

The premise of this line of reasoning is that people are more easily manipulated when their appetites are disordered. For example, if I desire to watch television more than I desire to be with my family, and spend my time accordingly, then my mind will be at the mercy of the networks, which, as many thoughtful folks realize, are controlled by corporate and State actors. Another example: if I desire to listen to other people (who are voluble) more than I desire to listen to God in prayer (who is silent), then I will fill my ears with noise in order to escape the silence, and buy a bunch of loud national corporate big-label music to do the trick. And another: If I desire to use pornography more than I desire to give myself to God or to my wife, then I begin to see people as objects for consumption and relationships as commodities and sex as a means for pleasure; the most intimate aspects of my humanity become negotiable and Market-able, and big-business items like porn and contraception and big-ticket political crowd-pleasers like abortion become not so absurd. Or consider how much easier the State can convince its people to go to war when they love petroleum energy and material comfort and security more than they love their enemies and those innocent people around their enemies who always suffer way more than anyone else in the bargain. Even something so simple as desiring junk food like chips and Pepsi more than the naturally healthy common Ugandan diet puts people into a corporately-dependent relationship; this may not seem significant to us, but food is a big deal here, comprising a majority of most peoples’ expenditures. The basic idea is that when people sin by loving a false image of the good (TV, bad music, porn, comfort, junk food, etc.) more that their good alternatives (human relationships, silent prayer, self-gift, self-denial, healthy food, etc.), they orient themselves away from God, Love, and the Good and towards other Masters. Everybody serves something; the choice is between a loving master who gives you freedom in return for your obedience, and a selfish master who enslaves and kills. Everyone makes their choice. The pitfalls of modernity are easy to make, and I think that without Church teachings on faith and morals to point out the traps, it is inevitable that people will persist along false paths towards destruction. Everybody makes false steps often, but the difference is whether or not we acknowledge our sin and turn back towards the way of goodness and truth. Those who can be permanently misled into false ways are the playthings of the powerful. Those who submit their affections and appetites to the purifying fire of the Sacraments and right doctrine have a chance, Lord-willing, of bravely resisting the foe.

(This, by the way, is why both the Right and the Left are both dead wrong. In simplistic terms, the Right thinks that the Market is a benevolent dictator, and the Left thinks that people’s passions are basically good. “Free the Market,” say the neo-cons, and the liberals want to unbridle everyone’s desires, no matter how potentially misled they are. Since a water-tight argument along these lines would take a book rather than this short cursory reflection, I will go ahead and make an appeal to the authority of various aspects of the Western Tradition and Church teaching in order to assert that they are both recipes for disaster.)

So now that Uganda faces the same modern tyrants that we do (the global corporation, the Empire, their own misdirected appetites, etc.), don’t you think that it behooves us to help them understand what they’re up against, and maybe even help them resist? I do. Otherwise, I think, they are dead in the water. Their tribal cultures have many arrows in their quivers and spears at their sides, but they need the heavy artillery of the Church in this war with big modern forces. My humble opinion is that the Church is the only really substantive countervailing institution in the face of modernity. Consider that there is no other entity more despised my moderns and more reviled and persecuted by almost every major thinker and government since the Enlightenment than the Catholic Church. A quote from John Henry Cardinal Newman about Her:

There is a religious communion claiming a divine commission, and holding all other religious bodies around it heretical or infidel; it is a well-organized, well-disciplined body; it is a sort of secret society, binding together its members by influences and by engagements which it is difficult for strangers to ascertain. It is spread over the known world; it may be weak or insignificant locally, but it is strong on the whole from its continuity; it may be smaller than all other religious bodies together, but is larger than each separately. It is a natural enemy to governments external to itself; it is intolerant and engrossing, and tends to a new modelling of society; it breaks laws, it divides families. It is a gross superstition; it is charged with the foulest crimes; it is despised by the intellect of the day; it is frightful to the imagination of the many. And there is but one communion such.

--An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine

Having the right enemies, of course, doesn’t make an institution good. What does make the Catholic Church good is that Jesus founded it, and said that the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. It alone offers the Sacrament of the Eucharist in its fullness, which is the most powerful manifestation of God’s humility, love, and power on Earth. And it alone presents a coherent cultural alternative to modernity. The Catholic Church offers a way of thinking about the human person and human life in their entireties; of understanding family life, civic life, and one’s role in the Church; of thinking about economics, poverty, birth, death, work, education, art, philosophy, music (OK, maybe not so much recently, but historically speaking the best music has been made by Catholics), not to mention sin, redemption, grace, God, and Heaven. To a superior extent, the Church incorporates doctrine and faith into a coherent, robust, thoroughgoing culture, a way of life. It answers the question, “OK, I am on board with the whole Jesus thing, but how then shall we live?” The people of the Church haven’t always, or even often, demonstrated the truly Christian way of living, but the answers are there. I think that in order to resist being subsumed into a secular, modern culture, it is not sufficient to merely deny that culture, but rather it is necessary to practice an alternative one. With the Sacraments, especially the Eucharist, at its source, the Catholic Church offers a truly Christ-centered, integrated, thoroughgoing, and incarnational alternative to modernity. The history of the Church for the last 500 or so years can be seen as an active rebellion against modernity, with much suffering and wounds to show for it.

So leaving the Ugandans to their own devices is not enough. But neither is leaving the Americans to theirs. We need the Ugandans in much the same way that they need us. This is the wealth of the Ugandan: he knows who his people are. He knows who are his family, his clan, and his tribe, and the bonds are sacred and permanent. Americans, by contrast, only rarely experience any thoroughly committed relationships. This is the way of modernity, to think and act like autonomous individuals rather than as members of a clan. One of my main lessons about life over the last few years is that the tribe is everything. When I have lived around long-standing, caring, committed friends, I have been happy. And I have been lonely, impoverished, and a shadow of a man when I have (briefly, thank God) been in contexts where I was alone and friendless, like when I was travelling. It turns out that one of the big secrets about life is as follows: always prioritize friendships when making decisions about where to live, what to do, etc.. This emphasis is what makes for happiness and provides the means to resist globalized consumerism. When you have your people, you don’t need as much stuff, and you can give the finger to capitalism. The Ugandans have the friendship and familiarity thing down. But through modernization, development, or whatever you want to call it, they seem to be at great risk of losing it. In the political realm, for example, the nation-state has an overwhelming interest in converting people from members of a particular tribe (Bugandan, Acholi, Karamojongi), with the full complement of communal identity and traditional roots, into members of the one national tribe as Ugandans. Just as the American Establishment liquidated the ethnic identities of the various European-American (Irish-American, German-American, Italian-American, etc.) tribes throughout the 20th Century by means such as the intentional disintegration of the Catholic ethnic enclaves via urban planning measures (see Jones, The Slaughter of Cities), so the Ugandan government employs various means to promote the national identity over all other forms of self-conception. In the process, the Ugandans are losing their tribal sense of being part of a people who have various strong allegiances and affinities with each other, predicated on blood and the land. They are moving towards a future of having one Master, in the State, whom they’ve never even met, and who doesn’t really care about them as individuals at all. And their relationships with each other are at risk of becoming so thinly attenuated as to be almost insignificant. I can say this with confidence because America has already gone down this road. The way that most people connect with each other in America is through a thin, national-scale, least-common-denominator culture, mostly shared through mass media in the form of watching the same sports, listening to the same corporate-produced national music, watching the same television shows, movies, and commercials, buying the same stuff, and talking about all of the above on corporation-controlled social media (Contrast this with the idea of a local culture and a local economy [click on the link for one of my favorite essays ever, by Wendell Berry]; it’s difficult to even imagine what such a culture and such an economy would look like, mais non?). We share nothing but what the powerful tell us to share; this malleability, in many ways, is what makes our economy and our State so strong. The State has an unimaginably powerful interest in keeping things that way; malleable citizens make for a malleable population, which makes for a supremely powerful State. In fact, the homogenizing forces (State-sponsored, corporate-driven, and otherwise) are so powerful that they spill over into other countries so that even they want what we offer, and everyone in the world is becoming American to some extent or another. The point for the current deliberation, though, is that when the sources of a shared life in America are so thin and meaningless (How could the least-common-denominator be otherwise?), then so are the relationships. Ugandans, on the other hand, have warm and deep ties because they share their lives together and still have small-scale local cultures and local allegiances; they have a lots of kids and live in big families (What makes people share life with other people more effectively than having to figure out how to live in the same room, house, and family with other people?), they stay married (What more purifying and self-less-ifying relationship could there be than marriage?), they live in crowded and intimately involved community lives in their cities and towns (You can’t swing a hyena without hitting someone in Kampala), they care for their old and sick and suffering (There are no nursing homes in Uganda), and they haunt each other even after death (Ugandans believe in a non-quite-dead-yet sort of afterlife where spirits roam around taking care of unfinished business, visiting people in their dreams, trying to find their way back to their home villages if their bodies are not properly buried there, etc.). The true interests of the people are opposed to the interests of the State in both Uganda and America, and the State is threatening to prevail in Uganda as it has already prevailed in many ways in America. If the people in either context prevail, it will be because they maintain their commitments to each other, in the context of coherent local traditions. But, as I argued above, they also need the strength of the Sacraments and the teachings of the Church in order to resist the State’s assault on human appetites.

[Side note:] The way that the State lures people away from their commitments to each other and to their communal duties is by appealing to the appetites for money, power, and pleasure. Geographically, this allurement takes the form of urbanization. In the city, people can think and act like autonomous individuals, whereas in the village they are inextricably part of a broader social fabric. T. S. Eliot’s haunting words come to mind:

When the Stranger says: “What is the meaning of this city?

Do you huddle close together because you love each other?”

What will you answer? “We all dwell together

To make money from each other”? or “This is a community”?

--Choruses from the Rock (click on link for full poem; well worth a read)

Without recovering local tribal cultures, like the Ugandan has, Americans will only plunge further down the path that the Ugandan is just now setting upon.

This deliberation is getting scattered and attenuated; I am bringing too many strands into this discussion--urbanization, local tradition, the State and appetite--to treat any one well. Let me try to pull it together a bit. My main point is that the trajectory of modernization in Uganda is away from a local, traditional, small-scale, tribal, coherent, relational mode of life in the village to a national, progressive, large-scale, State-centric, relativistic, individualistic mode of life in the city. The State and large-scale corporate entities have an interest in promoting modernization because the process severs people from competing allegiances--tribal, familial, religious, etc.. Whereas many consider modernization to be desirable and progressive, citing its capacity to alleviate material poverty, I argue that modernization actually introduces more profound and grave forms of poverty, namely relational poverty, spiritual poverty, and cultural poverty, among other forms. State and corporate interests lure people away from their relationships and duties by promising wealth, pleasure, sex, and enlightenment. One need only watch a few commercials and look at a few billboards to see how the logic of modernity proceeds--buy this car, and you will be like God. The way to resist this allure is by recourse to Jesus’ guidance and grace, especially through the teachings of the Church and her Sacraments. No other power in the world can effectively grant victory over the enticements of sin and the death that is their fruit. I do not think that it is enough for the Ugandans to attempt to go back to their local, tribal cultures. While they should certainly try to recover their relational way of living and the traditions and practices that sustained that way, they also need the power of Christ and his Sacraments and the wisdom of the Church to resist the allurements of sin in their own hearts and in their own cultures, and to resist the individualism that is the result of sin, along with all of the other traps of modernity. The temptations of the modern age are extremely powerful and potentially overwhelming; the Church is a bastion against them. Similarly, we in America need to learn from the Africans how to cultivate local tribal cultures. And we need to do it soon, before the African cultures disappear.

A great quote comes to mind, from Pope Pius XI:

When we speak of the reform of institutions, the State comes chiefly to mind, not as if universal well-being were to be expected from its activity, but because things have come to such a pass through the evil of what we have termed "individualism" that, following upon the overthrow and near extinction of that rich social life which was once highly developed through associations of various kinds, there remain virtually only individuals and the State. This is to the great harm of the State itself; for, with a structure of social governance lost, and with the taking over of all the burdens which the wrecked associations once bore, the State has been overwhelmed and crushed by almost infinite tasks and duties.

--Pope Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno.

For another pertinent quote from E. M. Jones, click here.

In much more superficial news, I found the most intensely sick, twisted, wicked, awesome acre of land in all of Africa today. Next to the PCAU offices is posted the following sign:

(Snake Park sign pic forthcoming)

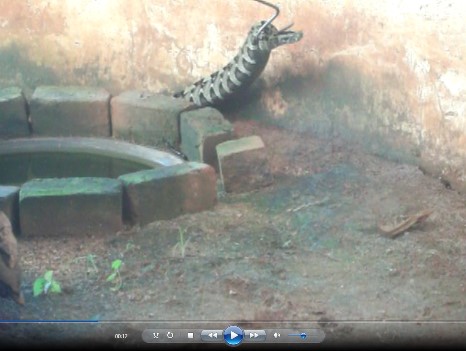

After a week or so of being intensely intrigued, I finally had time to follow the twisty dirt road on the back of a motorcycle taxi (“boda-boda” in Ugandan) to the place where the most accursed and fascinating creatures slither and smiles are even guaranteed (see bottom of Park sign pic). It was totally rad. There were fifteen or so little huts with plexiglass windows, along with five or six open-air cages. The guy kept on offering to take the snakes out so that I could get a closer picture, which offer I usually declined. In order to produce a more stimulating experience, the dude would poke the snakes to get them riled up and in a mood to strike. My boda-boda driver and I were the only people around, so we got a lot of showmanship and patience out of our guide. My favorites were definitely the Egyptian cobras (see pic below). They were HUGE. And pissed. And like blue and shiny. And really aggressive. PETA would certainly have a fit about this; I’m not so bothered, though, as I have little sympathy for serpents, their being so accursed and adversarial and all.

The Egyptian cobra (The pic does not convey scale [ha!] very well. Picture it six feet long, and standing about as tall as a mid-sized dog).

Here’s a Forest Cobra, which is, according to our guide, the most dangerous of all the snakes. These guys stand right up, about three feet high, and definitely mean business. Sorry about the glare.

And here’s a Rhinocerous Viper:

Please note the rhino horn:

Please note the rhino horn:

This is a photo series from a video that is amazing, but too big for posting. The idea was to fish a 15’ python from of the pond, drag it out, and then piss it off enough to make it strike.

The fishing:  The dragging:

The dragging:

The python strikes back:

Dragging attempt #2:

Dragging attempt #2:

Our guide dances around to elicit a strike:

Sick!:

Sick!:

The thing about pythons is that they have really sharp teeth, but they don’t inject (much) venom. Instead, the python latches onto its victim with its mouth, wraps its body around it, and then squeezes the hapless sap until it cannot inhale.

And finally, the guy dragged a regular old viper out of its cage for a brief little slither. A few facts about the family Viperidae follow, for your herpetological enlightenment. Contrary to popular depictions and branding associations, the vipers are usually a rather sluggish and uninspired crew. This guy was no exception. Another surprising viper fact: they give birth to slithery snake babies instead of snake baby eggs. In fact, the word “viper” is derived from the Latin words vivo = “I live” and pario = “I give birth.” Unlike the python, vipers do inject. A word about viper venom from the Wikipedia article entitled “Viperidae”:

“Viperid venoms typically contain an abundance of protein-degrading enzymes, called proteases, that produce symptoms such as pain, strong local swelling and necrosis, blood loss from cardiovascular damage complicated by coagulopathy, and disruption of the blood clotting system. Death is usually caused by collapse in blood pressure. This is in contrast to elapid venoms that generally contain neurotoxins that disable muscle contraction and cause paralysis. Death from elapid bites usually results from asphyxiation because the diaphragm can no longer contract….

Proteolytic venom is also dual-purpose: firstly, it is used for defense and to immobilize prey, as with neurotoxic venoms; secondly, many of the venom's enzymes have a digestive function, breaking down molecules in prey items, such as lipids, nucleic acids, and proteins. This is an important adaptation, as many vipers have inefficient digestive systems.”

Out for a slug-like, creeping slither:

Not actually like this:

Not actually like this:

The grab:

For your sense of scale [!]:

For your sense of scale [!]:

In the morning, I attended a PCAU monthly conference. This month’s theme was the ethics of palliative care, which you’d think would be really interesting. Or rather, I would think would be interesting…for me…given my interests in bioethics. I expected, though, what was actually the case, namely that the presenters would merely pull a page out of the Principlism handbook and follow it to a letter. Chalk another one up for Beecham and Childress, all the way over here in Africa. (Sorry; I am being a little bit inside here. B and C devised a way to reduce all bioethical considerations to four words, namely Autonomy, Beneficence, Non-maleficence (sounds redundant, huh?), and Justice. Bioethics on a business card. It’s totally lame and wildly popular. They make gajillions of dollars publishing texts and hosting seminars to train all manner of medical professional in their method, which amounts to bureaucratic procedure calculated to promote patient autonomy above all else, especially above any absolute normative ethical standards; the parties deliberate about the four principles until autonomy rises to the top and the patient or the proxy makes a decision that might or might not be a good one. But who is to judge when absolutes are out the window?).

5.31.14

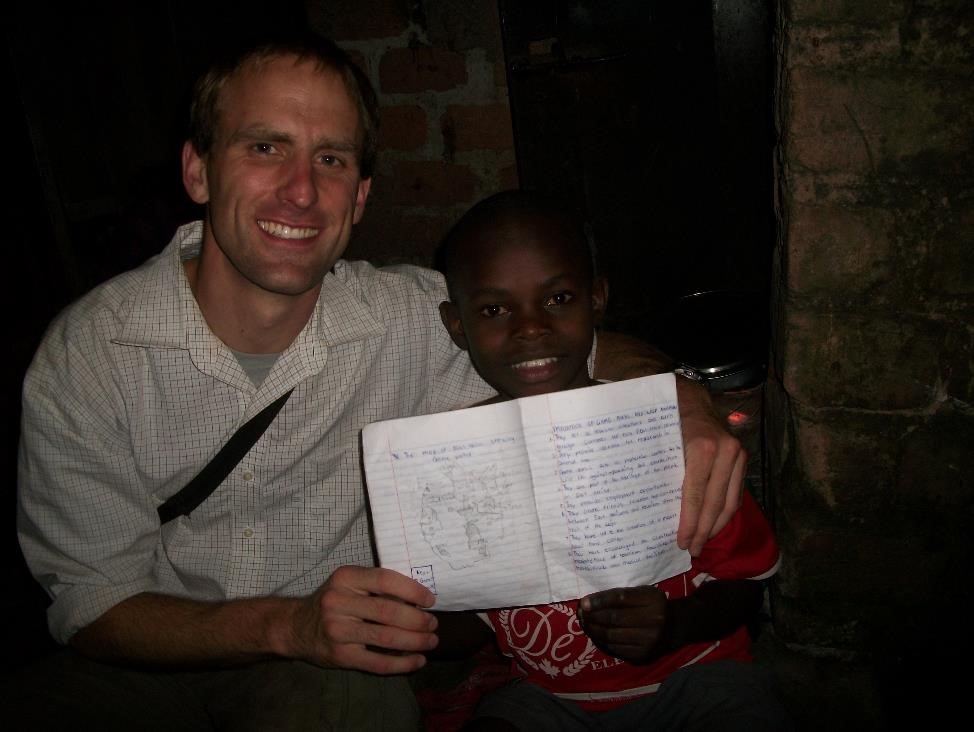

This evening was the best time so far in my trip, and maybe for the past few years or my entire life. Whoa. Yeah. The apex was sitting on the floor in a 10x10 concrete room with 20 street boys, one candle, and my Ugandan friend David on the electric piano leading praise and worship in Luganda while the boys sang and prayed their hearts out. It was the beatific vision. Or maybe the closest I’ve come so far.

I ran into my South Bend friend Brittany and her Ugandan friend David on a rafting trip last weekend. She told me about her street friends in Kampala and welcomed me to come and see, so naturally, I made an excuse to move there for a couple of weeks. We met close to my place, and made our way to the slums of this already slummy city; so, like, the slums of the slums. The kids. Oh, the kids. My heart is full of them right now, so it’s kind of difficult to get it all into words. But I’ll try for a bit. One of David’s friends lives in the slums and opens his house to 20 or so of the boys for camping out at night. We went to his house, met some kids briefly, and then made our way to a slum market place where a bunch of high-school-aged guys flocked around us and introduced themselves. The really heartbreaking thing is that almost all of the guys over 13 or so were high on glue and gasoline fumes. They carry it around in small water bottles tucked into their sleeves and sniff it constantly to stay buzzed. So tragic. Some of them were really bombed out, while others were just sort of hazy. They all wanted to talk to the m’zungus, and we carried on for about half an hour. Then we walked through a field at an elementary school where a lot of the dudes hang out and play soccer and stuff. I got into a tug of war match with a few of the younger pre-adolescent guys who were not high and a lot of fun. I gave a lot of shoulder rides. We made our way back to the slum house, and served some dinner that we had grabbed on the way over. The playing got a lot more fun as the regular crew of 20 gathered for their weekly Saturday night bible study. Lots of learning elaborate handshakes and tickle attacks and stuff like that. Some of the guys just wanted lean on me and have an arm around them. One of the dudes asked for a back massage which became the cottage industry for the rest of the evening. The waiting list remained healthily populated until I left. The bible study started up with about 40 minutes of P and W, wherein the boys really belted it out, prayed so much and so hard, and lifted their amazing huge/little hearts right up to Jesus. Then one of the leader types gave a lesson, they prayed and we went. The whole thing lasted an hour and a half or so. Heaven on earth.

I will make these boys and boys like them a big part of my life somehow.

I had the opportunity to talk to David about the boys and their backgrounds a bit at dinner beforehand. David is about 21 and has been working with the dudes for about 5 years. He is a really serious and sincere Christian, and has a tremendous commitment to the guys. He grew up an hour or so from here. I asked how they end up on the streets, and he said that a lot of them have run away from home for various reasons. Many of them experienced abuse in their homes, either beatings or sexual abuse. A lot of the kids come from poor backgrounds, predictably, but others come from wealthy backgrounds where they were mistreated. I also asked whether any of them make it off of the streets, and David responded that when they do, it is usually through church involvement. Much, much more could surely be said about everything, and perhaps I will learn more as I try to work with the kids more and more.

Praise Jesus! Please pray for these guys! Like crazy! I don’t know a lot of their names at this point, but I will try to share some names and profiles as I (hopefully) get to know them better.

General note: You might have noticed that I haven’t been talking much about my work. There is a reason for that. I don’t yet know how to present the stuff that I have seen to a general audience. Suffering and pain and really personal and intimate interactions with people are sort of dear and private and sacred, and I haven’t felt comfortable spouting off about them in public yet. If you are interested, feel free to shoot me an email asking about the people and the work. I will hopefully be able to express myself better in the privacy of a personal conversation, and that process might help me figure out how to talk about things on this journal.

6.2.14

I got violently ill last night. It was/is one of the best things that could have possibly happened to me. God laid me flat, and I so needed it. I’ve been wanting to pray more, needing to pray more, but haven’t done it. There’s nothing like sleepless nausea and endless bathroom trips to bring us to our knees, in all the possible senses. I prayed the name of Jesus constantly, and for all of you, and for God’s will in all of this totally nutzo stuff He’s been revealing to me over the last few weeks. The hospice patients, the street boys, the life, the career, my family and tremendous friendships, everything. So good.

Yesterday I had two great convos that I will mention briefly, if only to bookmark them. The first was at lunch with Br. Francis, an 80-or-so-year-old member of the White Fathers community in Kampala, with which I am camping out these days. The main topic of the convo was development. Br. Francis is from the Netherlands originally, but has spent the last 50 years or so (!) all over Uganda as a missionary. His work has been focused on giving people the education and tools that they need to run sustainable farms and to work in various technical professions. He’s started many operations all over the country. One of the most interesting principles that he brings to bear on his work is that he tries to avoid using western money. For instance, somebody recently offered him around 250k Euro for his work; he only took about 12k of it. His rationale is that the people can’t maintain the big ticket items that the big donations buy. Big buildings and fancy new machines end up being more of a burden than help. On the other hand, if the people have to work for the money to buy the stuff, or go into a bit of debt for it, they buy only what they actually need and what they actually can use and maintain. For example, the western mentality decreed in 60’s that ox carts were backwards, and that it would be a big help to the people if we bought them some trucks. But when things fell apart under Idi Amin Dada, the trucks became useless as the infrastructure needed to maintain them disintegrated (petroleum lines, repair shops, parts manufacturing, etc.). By that point, the ox cart infrastructure had also been scrapped, along with the good jobs that constituted it (blacksmiths, wheel-coopers, carpenters, etc.). So, thanks to well-meaning, but ill-conceived, western aid, the people were impoverished even further. Br. Francis has a prophetic sensibility, born of years of hard experience, that people shouldn’t own what they don’t earn. Another anecdote: he spoke of living in a bus on a farm property for a year or so as the farm was starting up. The idea was to make the farms productive first, and only then, to buy houses with the hard-earned money. This way the people avoid debt and make good decisions about what sort of house they can reasonably afford to build and maintain. Br. Francis also spent a large part of his career setting up and teaching in vocational schools. He mentioned that the five main subjects were metalworking, carpentry, mechanics, electricity, and plumbing. Br. Francis did all of this in connection with the charismatic movement, which connection doesn’t make much sense to me, as I am totally unfamiliar with the idea. But what came across when Br. Francis was talking about the movement was that he thought it important to de-emphasize the emotional aspects of charismatic experience, and subordinate them to fruits of peaceful and quiet contemplative prayer. What a tremendously life and a fabulous man!